Domestic turkey

Holidays

Thanksgiving

Turkey Drover Spirit

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

Our Thanksgiving turkey, hermetically sealed in its plastic wrapper, defrosts in my kitchen sink. With luck I'll remember to pull out the frozen bags of bread before I go to bed tonight. (I've been saving the heels and mangled leftover pieces of bread for most of this year in one of my many attempts at being thrifty.)

And although I've spent the last two hours reading e-mail, checking blogs, and posting comments, and am now several hours behind schedule, I may find time to de-string the celery and put together some of the side dishes for tomorrow's feast this evening.

And although I've spent the last two hours reading e-mail, checking blogs, and posting comments, and am now several hours behind schedule, I may find time to de-string the celery and put together some of the side dishes for tomorrow's feast this evening.

Uh-huh. Right. I'll be doing good to get a shower today at this rate.

I made a frenetic drive to the superstore yesterday for supplies. I wanted to do the "made do with what you have" plan I suggested Monday, I really did, but mentioning it provoked a minor mutiny. Plus, my parents are coming up, and there are just certain ... requirements ... to be met.

How old am I, anyway? At what point in my adult life will I stop trying to live up to those unspoken expectations?

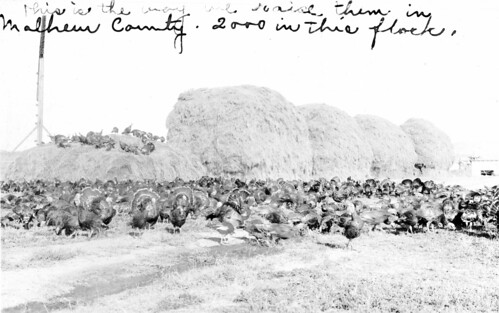

In the light of our pre-feast shenanigans, I thought I'd share an odd bit of history about the turkey drive. According to oral histories, during the 1800s domestic turkey producers copycatted the cowboys of the day in getting their wares to market. In Vermont it was quite the social event, according to an interview with Peter Gilbert on Vermont Public Radio.

Before railroads, the only way to get turkeys from Vermont to market in Boston was to walk them there. And that, throughout much of the nineteenth century, is exactly what Vermonters did, including Vermonters from the northern-most parts of the state. Townspeople put their birds of a feather together, and, accompanied by wagons with camp supplies and tons of feed grain, they escorted as many as 7,000 birds at a time all the way to Boston. Drives of three to four thousand birds were common in the 1820s and ‘30s. Historian Charles Morrow Wilson says that about 1,000 birds was the minimum necessary to make the150 to 350-mile trek worthwhile. It was a long haul. The flocks could make only ten to twelve miles a day, and at least one drover was required for each 100 birds.

Boys scattered shelled corn feed in front of the birds, so they would walk forward, while others herded from behind. Flocks might spread out for more than a mile, ranging in width from a few feet to fifty yards. To protect the birds’ feet on such a long hike over rough terrain and November’s frozen ground, Vermonters sometimes coated the birds’ feet with warm tar. They lost about ten percent of the turkeys to forded rivers, fox, hungry farm families they met in route, and other perils of the journey.

Two key facts to keep in mind are: big birds, little brains. Wherever they were when the sun set, that’s where they perched for the night. Their collective weight shattered trees. Occasionally, so many birds perched on a farmer’s shed or barn that the building collapsed. They sometimes mistook the shade of a covered bridge for dusk and simply stopped. And so the drovers would have to go in, pick them up, carry them through the bridge and into the sun, where they’d perk up again and head on their way.

The advent of railroads and then, in the 1850s and ‘60s, refrigerated box cars were the beginning of the end for the great turkey drives, but some lasted into the twentieth century. The notion, in the twenty-first century, of driving thousands of turkeys, or even two birds on a leash, from Island Pond south all the way to Boston is charming in its absurdity.

And poultry producer Norbest provides this information on their "turkey trivia" page (an excellent source of conversation topics around the dinner table tomorrow!):

In the early West, turkeys were trailed like cattle in "drives" to supply food where needed. One of the earliest turkey drives was over the Sierras from California to Carson City, Nevada. Hungry miners coughed up $5 apiece for the birds.

While the idea of being a turkey drover doesn't stir the romanticism of the early American cowboy, or the quaint pastoral image of the shepherd with his sheep, it does remind me of something to be thankful for this holiday: American ingenuity and determination.

Politics, the economy, and religion (topics we should avoid discussing with relatives during a holiday meal) are subjects likely to come up tomorrow as we wile away the hours between turkey and pie. If the conversation begins to veer toward negativity, tainting the holiday joy with conspiracy theories and general sour grapes, share the story of the turkey drovers.

America has always been, and will continue to be, a place where people -- since the Pilgrims and the Indians celebrated that first Thanksgiving meal at Plymouth -- adapt to their circumstances, apply their faith, and accomplish the impossible.

America has always been, and will continue to be, a place where people -- since the Pilgrims and the Indians celebrated that first Thanksgiving meal at Plymouth -- adapt to their circumstances, apply their faith, and accomplish the impossible.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=6be6f7d9-f8f9-468e-836c-c426e228a417)

4 Comments

Have a wonderful holiday tomorrow, Niki! I love the Vermont story... what a hoot!

ReplyDeleteHope your holiday is great -- and hope we both get a nap (maybe Friday? It's worth wishing for!)

ReplyDeleteNow that was something I never knew. Guess one is never too old to learn. Thanks for sharing that fact about history. Happy Feast day to you and yours and say hi to your parents from us!

ReplyDeleteI just realized I never commented back! I'm so sorry! Thank you, Tess, Susanne, and Sandy! I hope you had a wonderful Thanksgiving. Now, on to Christmas! Whew.

ReplyDelete